Savoring Heritage

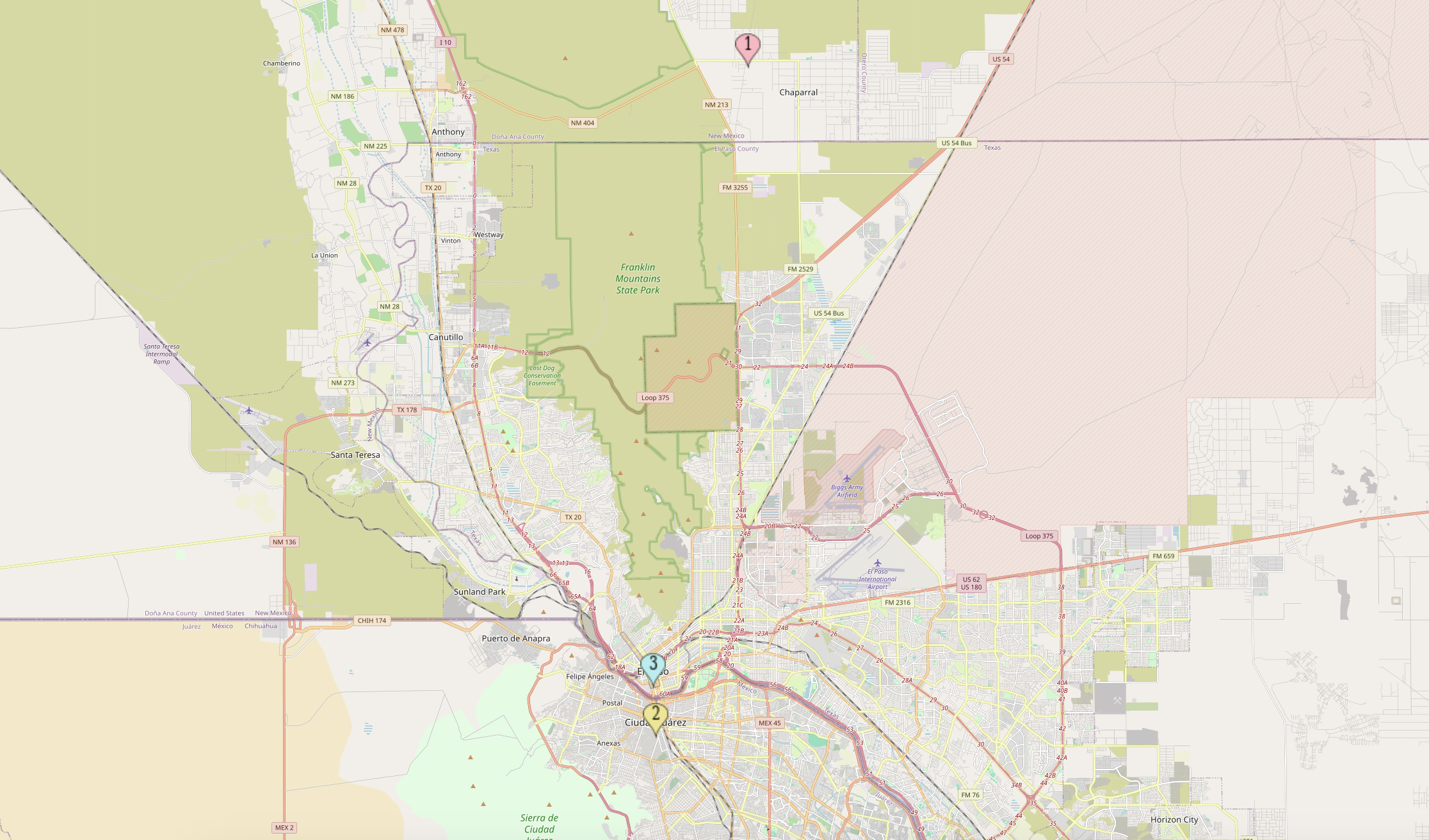

I like to joke that my family immigrated “from Mexico to Mexico II.” My hometown, El Paso, Texas, conveniently sits between two borders: Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and Chaparral, New Mexico. I also like to think that my great-grandpa is responsible for half of Chaparral’s population.

The proximity between Chaparral (1), Juárez (2) and El Paso (3). (Map generated by Gabrielle Lopez via Mapcustomizer)

In his twenties, my great-grandpa, Roberto Mata, hustled as a carpenter in Juárez. He had the opportunity to move to Virginia with the benefit of automatic citizenship, but Chaparral offered greater benefits: cheap land and proximity to the El Paso-Juárez border. He also stayed to marry my great-grandmother.

He passed his carpentry skills down three generations. It’s rare to see a house in Chaparral without “Mata” stamped on the mailbox. My great-grandparents’ house became the family hub, which was convenient for celebrations.

Our greatest tradition happened every Nochebuena, or Christmas Eve. The entire Mata family would cram into my great-grandpa’s house. Each room had its own activity centered around food. The kids played lotería in the living room, a game similar to Bingo, and used raw beans as markers. The uncles discussed the family’s carpentry-turned-construction business over tamales. Tamales, the staple food for the holiday season in Latin America, are steamed corn husks stuffed with maize and any protein.

Tamales range in flavors but the most common are red (salsa), green (salsa) and sweet. (Photo via Food.com)

My aunts ran the kitchen like it was the Navy. They would multitask gossiping, cooking and serving. The only time they stopped would be when my great-grandpa’s wheelchair whirred into the room. As he aged, he talked less and instead observed the family he started.

I never saw him outside a blue plaid flannel, grey sweatpants and brown slippers. Even inside the house, he wore his signature accessory: a grey cap with an embroidered rooster. He always parked his wheelchair with a diagonal view of the fireplace, which was useless as it was stuffed with trophies, each topped with a golden rooster. My great-grandpa dabbled in cockfighting until the United States illegalized it in 2008. What many view as animal cruelty became our family symbol.

My great-grandpa’s cap from Palenque La Hacienda, a cockfighting ring based in Juárez he often participated in. (Photo via Gabrielle Lopez)

Our family acknowledged Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) but never built an altar to commemorate lost ones. Rather, we celebrated my mother’s birthday.

For her 50th birthday, my sister decided to organize a Día de Muertos-themed party. Over the years, our annual Nochebuena gathering shrunk as the younger generation of cousins moved out of the El Paso area. My sister hoped a big party would make an excuse for everyone to reunite. With the amount of family members invited, we switched from cooking to ordering catering.

On the morning of my mom’s party, I woke up to the sun still set. At first, I thought it was restlessness but realized I woke up to murmuring from my parents’ room.

I rolled to my side and picked up my phone to check the time — five in the morning. Out of habit, I opened Facebook instead of trying to fall asleep. I did a double-take on the first post of my feed.

“Please forgive us folks as we are canceling my wife’s 50th party. Her Grandfather passed away this morning. Please let others know and send her prayers.”

I heard my parents shuffling down the hallway. I hid my phone under my pillow and pretended to be asleep. Waiting for the door to open, I mentally rehearsed how I would react to the news I pretended not to know.

Despite living 35 minutes away from Chaparral, we were the second family to show up at the house, but when half the family were neighbors, it didn’t take long for the house to fill up. I recognized cousins I hadn’t seen in three or four years. As we made greeting rounds, we received apologies for canceling my mom’s party.

My grandma and great-aunts — my great-grandpa’s daughters — scrounged the kitchen for ingredients to provide enough meals for almost 80 cousins. A few cousins came to the rescue with boxes of Mexican pastries, but they could only buy so many.

A lightbulb could have appeared over his head with how suddenly my dad’s face lit up.

“We still have the tacos we ordered for the party,” he said. “It’s the perfect amount!”

The restaurant we ordered from was conveniently located about 15 minutes from Chaparral. I helped my dad pile trays of corn tortillas, shredded beef and various vegetable toppings. The smells of onion, spice and maize made my stomach rumble.

All the cousins parted like the Red Sea when we returned with food in our hands. The aunts quickly cleared a space for the trays and stacked plates at the end. Once everyone had a plate, the food’s warmth cleared the house of somberness. Conversations turned from condolences into memories. According to one of my uncles, my great-grandpa’s friend framed him for robbery and got him arrested in Juárez.

Of course, our hearts ached for losing the head of our family, but there was something powerful about how we celebrated. My grandpa’s death day showed us the beauty of our Mexican culture. From our tamales to tacos, we ate specialized foods together at my great-grandparents’ house. For me, shredded beef tacos always remind me of the day I saw most of my family lineage under one roof.

Most importantly, beef tacos remind me of the day I started properly celebrating Día de Muertos. My sister and I set up our first altar in our living room to honor and welcome our relatives back to the living world. We printed pictures of previous family members we lost and kept our great-grandpa at the center.

My family’s first proper Día de Muertos altar with my great-grandpa’s photo to the right. (Photo via Gabrielle Lopez)

From the bustling Nochebuena gatherings to the somber yet celebratory Día de los Muertos, I cherish these moments of connection and remembrance through food. I profoundly appreciate having a family and space that taught me to embrace my heritage. Reflecting on my great-grandpa’s passing showed me that providing food for the family is second nature.

Original story and images published on Medium

Cover image collected by Gabrielle Lopez